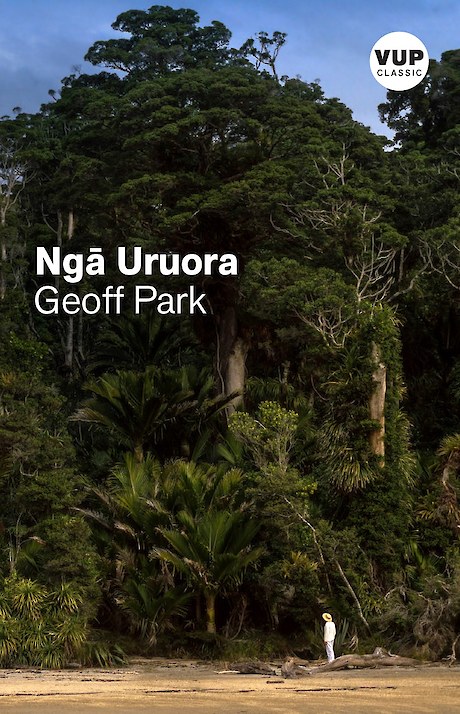

First published in 1995, Ngā Uruora took the study of New Zealand’s natural environment in radical new directions.

First published in 1995, Ngā Uruora took the study of New Zealand’s natural environment in radical new directions.

Part ecology, part history, part personal odyssey, Ngā Uruora offers a fresh perspective on our landscapes and our relationships with them. Geoff Park’s research focuses on New Zealand’s fertile coastal plains, country of rich opportunity for both Māori and European inhabitants, but country whose natural character has vanished from the experience of New Zealanders today. Beginning with James Cook’s Endeavour party on the Hauraki Plains, and then the New Zealand Company’s arrival in the valley that became the Hutt, Park takes us through the river flatlands where the imperatives of colonial settlement transformed the original forests and swamps with ruthless efficiency.

Ngā Uruora’s primary journey is to four auspicious places – Tauwhare on the Mōkau River, Papaitonga in Horowhenua, Whanganui Inlet and Punakaiki on the South Island’s West Coast – where small remnants of the plains forests’ indigenous ecosystems of kahikatea and harakeke still survive. The histories of these places, what they mean to Māori, their ecological vulnerability and their significance for conservation are major concerns. Park ties these issues together through the experience of the places themselves, their magic, immediacy and beauty.

Dr. Geoff Park was born in 1946 and grew up at a quintessential edge of the Empire – between the primeval forest and the antipodean suburb. A passionate childhood curiosity with the former led to university training in ecology and a career as a Crown research scientist, and then Concept Leader Natural History at The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, before becoming an independent ecologist and writer. His second book, Theatre Country: Essays on Landscape and Whenua, was published in 2006. Constantly underwriting his ecology was the realisation that while New Zealanders are blessed with national parks and wild mountains, few have any idea of what happened to our nature in the lowlands. He passed away in 2009, leaving us a legacy of deeper appreciation of our own unique ecology – and the value of these last remaining wild fragments.